‘So you are going to sit here and you’re going to play the piano for us. The moment you can’t go on anymore, is the moment I put this shotgun to the back of your head and pull the trigger. Am I making myself very clear?’

Joseph nodded. He sat down and looked at the piano.

‘Here. We’ll even let you look at your son while you’re playing. I mean, we are not animals. You’ll appreciate that.’

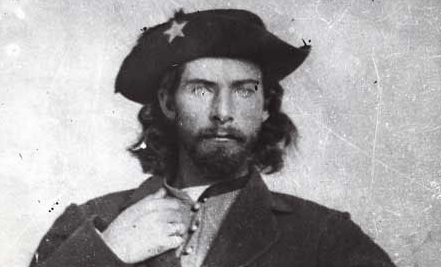

The invader put a tiny picture of a man in uniform posing with a gun on top of the piano.

‘That’s his son’, the man, clearly the leader, said to the other five guys who had broken into his home a few minutes ago. It felt like an eternity.

‘He’s in the army.’

Joseph wondered why that needed being said. It was obvious to all.

They had bound up and gagged his two servants.

‘We’ll let you go after we’re done schooling your master’, one of them had said.

The leader slammed Joseph hard on both shoulders.

‘Play!’

Joseph started playing. One of them, he looked like the youngest of the bunch, was incessantly chewing tobacco. He quipped: ‘Oh Lordie, that’s some hellish piano playing. I don’t know who we’re torturing here. Him or ourselves.’

One of the men got up and walked off very briskly. The leader went after him. Joseph couldn’t hear what they were saying.

On the back porch the leader asked what was going on.

The man, 32 years old, a shopkeeper who had sold school supplies, books, postcards, etc, before the war shook his head.

‘This doesn’t sit right with me, Leon.’

The leader of the band had been named Leon by his father. Leon’s father had been an obsessive student of all things war. He had named his son after the Spartan king Leonidas.

‘What doesn’t sit right with you? Didn’t you see? His son is in the reb army.’

‘Yes, but the father isn’t.’

‘Take a look around, George. Take a look around. How many acres does this man own? Look at those fields. You see those slave cabins there? That’s who works these fields. They pick the cotton. Why would you let a parasite like that live?’

‘If I met him on a battlefield, sure. But to murder him in his home… And then in this way. Why make him play the piano first?’

‘Do you think he never whipped one of his negroes to death? Why do you think they don’t come to his rescue? They must hear us. They’re staying in their cabins. They don’t care about this tyrant that got fat and rich on their blood and sweat.’

‘I don’t know, Leon, I really don’t know. Am thinking of signing up with the regulars.’

‘The regulars are run by idiots. There’s been another defeat. At some place called Chancellorsville. Everybody gets a go at Bobby Lee and they all run with their tail behind their legs. Now Lee is plundering Pennsylvania.’

‘Our armies have met with success as well. They’re operating against Vicksburg. If Vicksburg falls the Mississippi will be closed to the Confederates.’

‘So what? How many miles away is Bobby Lee’s army? His base is in Virgina. He don’t care about no Mississippi. Besides, have you been to Vicksburg? I was there once with my daddy. That place is impregnable. Am telling you, George. You can’t drive out slavery unless you kill all the slave owners, one by one. Only way to free this land of that scourge. Suppose they lose this war, which don’t look like it, but suppose they do. Their blood sucking mentality ain’t gonna melt away over night. These vultures are still gonna be vultures. Even if you officially abolish slavery. I say, we kill them now. Before those yellow-livered bastards in Washington get too scared and make a deal. Or before France and England invade to save their dear slave-holding friends.’

‘I don’t know, George. Sometimes I think you just enjoy murdering people.’

‘Say that again?’

‘You heard what I said.’

‘You better watch yourself, George. I ain’t no murderer. If nobody be having slaves I’d be murdering nobody. Not a soul. You got that?’

‘Sure, Leon. I got that.’

Joseph played and played and played.

George stayed out on the porch. He hoped Joseph would play for so long something would happen that would make Leon’s irregulars have to skedaddle.

He kept staring at the slave cabins in the distance. There was day light now, but not a single occupant had ventured out. George started wondering if they were even there. Maybe they had all already run off. He considered going over and taking a look. Maybe asking about what kind of master Joseph had been to them. Maybe they’d tell him awful stories. Maybe they’d show him scars from whippings. Or worse. A chopped off foot here and there. Punishment for an escape attempt. Maybe that would make it easier to accept Joseph’s imminent death. George got up.

There was no more music. The silence fell on George like a cold breeze.

He heard Leon call out his name.

‘George, come on in. Where the hell are you? The show’s about the start.’

George shook his head, took a good look at the slave cabins, sighed and returned inside.

He saw Joseph sitting at the piano, his arms hanging by his sides. He’d never seen a man look so tired.

‘5 hours’, said Leon. ‘5 hours! Not bad for an old guy!’

The other men clapped and cheered. One wanted to shake Joseph’s hand to congratulate him, but he couldn’t lift up his arm. He just sat there, staring at the picture of his son.

‘What is the name of this fine looking lad?’, asked Leon.

Joseph mumbled: ‘My son’s name is Michael.’

‘Michael is a fine name. Did your wife choose that? Where is your wife anyway?’

Joseph didn’t answer.

Leon took the picture and ripped it up.

Then he said: ‘George, take the shotgun and send this slave owner to be judged by his maker.’

George was perplexed.

‘Me? I’ve told you, I don’t feel right about this.’

Leon turned to the others under his command:

‘Boys, our George here has doubts. Do you have any doubts?’

The others all let out a clear ‘No, Sir.’

Leon said: ‘See? The others don’t have doubts. Maybe we misjudged you. Maybe you’re dreaming of buying yourself a nice piece of land and saving up to get a few slaves of your own.’

‘I hate slavery with every fibre in my body. It’s a moral evil.’

‘Prove it. Send Joseph on the road to eternal salvation. If not, we will have to review your enlistment and your allegiance.’

There had been no enlistment, because they were irregulars, but George knew what he meant. Leon was about to kick him out of his gentlemen’s club. George couldn’t know for sure if Leon would let him go alive. He was his favorite, but that didn’t mean much. He had seen Leon hang one of his own slave-owning cousins in an apple tree. Leon told George they had climbed the tree together as kids.

‘Don’t make me do this’, said George.

Joseph smelled his chance now that there was a rift between the invaders. He fell to his knees and pleaded for his life. He claimed that he’d always treated his slaves humanely. That he had never broken the law. That they should ask his house servants. That secession was legal, but that he had spoken out against it.

Leon and George’s eyes locked.

Leon studied George’s face intently and decided that his favorite wasn’t going to do it. He would have to punish him for disobeying a direct order, otherwise the other men could start questioning his authority.

Leon put the barrel of the shotgun against the back Joseph’s neck and pulled the trigger. The head got blown clean off. There was blood and brain matter all over the piano.

They looted the house and put everything of value into their saddle bags.

Then they freed the two house servants, sent them outside and torched the main house.

George did the most work when it came to burning the house. He had doubts about that too, but at least it wouldn’t kill anyone and it might redeem him in the eyes of Leon.

Two weeks later George tried to leave one morning as they were camping in the woods down in Arkansas, about forty miles north of Little Rock. He intended to sign up with the regulars. The army was always in desperate need of recruits. He longed for a fair fight. Soldier to soldier. Rifle against rifle. The cunning of the commanding generals played a part, of course, in the outcome, but at least no unarmed men were being shot.

Leon caught up with him after two days.

He made one of the other men shoot off three fingers off of George’s left hand. The army would never take a man like that. Can’t load a rifle like that.

So George went back to being a shop-keeper.

For years he handed out free copies of the novel ‘Uncle Tom’ to any customer who walked into his shop. Also the autobiography of Frederick Douglass. ‘Narrative of the life of Frederick Douglass, an American slave’, published about twenty years before the outbreak of the war.

Most didn’t want it. He suspected that some who did take a copy might be using it for other purposes than to read it.

George could never decide if he had been right about not wanting to participate in Leon’s killings. He often felt like he hadn’t been radical enough. His wife, a woman from Boston, who he had met when she was visiting her sister here in town, in southern Illinois, later told him: ‘I don’t think books alone can stop evil.’

He asked her if she would have killed Joseph.

She claimed she would have.

‘It would have been wrong, absolutely, but to not kill him, would also have been wrong. More wrong than not killing him. Those former slave owners are taking over the country again. They’re recreating slavery in anything but name.’

He found peace after he found out, in 1875, ten years after the war, that Leon had gone into Indian territory after Lee had surrendered in April 1865.

Leon was making his money as a scalp hunter. He butchered Native Americans and sold their hair. George found out you could get up to 200 dollars for one Indian scalp.

That concluded the matter in George’s mind.

Leon did kill for sport.